An Interview With Matthew Polenzani

Recently, I had the pleasure of speaking over Zoom with the splendid tenor Matthew Polenzani about operatic characters, his happiest memories as a performer, the Chicago Cubs, fatherhood, and more! Matthew is not only one of the finest tenors in the opera world but also one of the most beloved, and I found out why the very first time I met him in 2018. Read excerpts from our interview below or watch the expanded video above. Enjoy!

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Violette Leonard: First off, Idomeneo is your favorite Mozart opera — you're so wonderful in it — and you've said that you connect with him especially well because of your shared fatherhood. How do you connect with characters you have less in common with, like the Duke in Rigoletto or Ernesto in Don Pasquale?

Matthew Polenzani: Well, a lot of that comes down to imagination, and of course, when you do your homework regarding a character's background, and where they came from, and how other characters relate to them, it gives you clues as to how you think that the person I'm playing should behave. In the case of somebody like the Duke, I don't think of him as only a cad, I don't think of him as only a womanizer. That's really the side of him we get to see the most of, but I do like to try and put my claws into the top of the second act aria, “Parmi veder le lagrime," because this is a moment where he acknowledges that the possibility of love exists, and that it might even happen for him. It's short-lived, obviously, but I would like to think to myself that at some point, maybe as he gets older or whatever, maybe he'll find somebody who really turns the key to his heart, so to speak, and gets him going. In the end, a lot of it just comes from thinking about or wondering about or imagining how somebody might react in a situation when something is said to them. Each time, hopefully you get a little something new, a little deeper insight into character.

Werther is your favorite role to sing. Why is he special to you?

Well, it's funny, a big part of it has to do with the music, which somehow touches my heart in a different way than other things. I also have dearly loved Nemorino [in L’Elisir d’Amore] in my career, and “Una furtiva lagrima" is a great aria, it's a touchstone aria and a tenor showpiece and etcetera. But there are things in Nemorino that, if I never sang again, it wouldn't change much for me, you know? There's virtually not a single note in Werther that I would say to myself, “Well, if I never sang that again, I wouldn't care." It touches something in me deeper than other things and beyond that, I love this guy for the purity of his love for Charlotte and how divided he is against himself, against Albert, against her in some ways, how he has multiple things pulling at him, but he's got this deep, dark, true desire for Charlotte that he can't figure out how to overcome, and I love him for that purity. I love him for his humanity. We all have divisions inside of ourselves, and he fights all these things to a point where he just realizes he can't keep fighting, which is a terrible sadness, and no human should ever find themselves in those shoes.

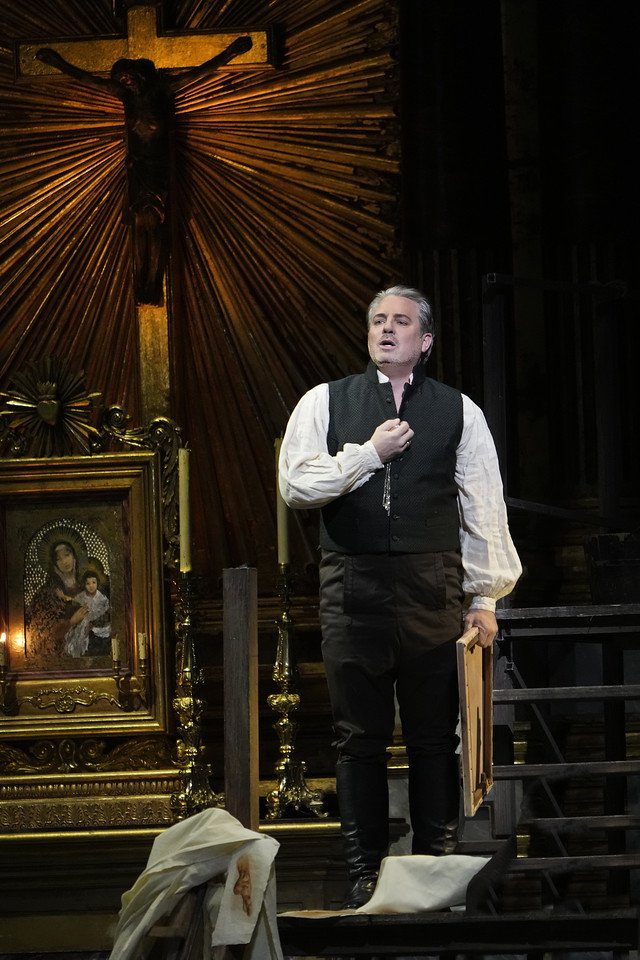

You just finished a run of Tosca at the Met, as Cavaradossi. You only debuted that role last June. What's your journey been with the character?

Matthew in Tosca (Ken Howard/Met Opera)

Well, it's a short journey, obviously, since I've only sung it twice, but I do think I've gotten a pretty good clue about who the guy is. One of the things that I really discovered in these couple of runs: I've really gotten to understand the duality of Mario Cavaradossi. Something that I didn't really understand about him was his secretive nature, his spy nature, the nature of somebody who has hidden people before and has a place in the well of his home, where people can be hidden, safely, without being found. This is a guy who has clearly done this sort of thing before. He was an intelligent guy who lived a very dangerous life. This is a guy who's a man of action, this is a guy who is driven by something bigger and deeper, and I really enjoyed chewing up the duality of his persona.

You made me cry so much after “E lucevan"!

Yeah! Well, Puccini can do this. I'm telling you, if Puccini was alive now, John Williams would have a major-league competitor. He writes very cinematically, and Puccini detractors often say, “Well, he's too obvious, he's obviously just plucking heartstrings and it's so over the top," and man, but that's what I love about it, and like I say, for people who don't like it: hey, that's totally cool by me. Love what you love, and I'm down. But one of the things I love about that music is that he cleaves right to the center of the heart, and he knew how to write with a surgeon's precision, to make sure you felt everything of the moment. I'm a big, big proponent of that music. I really love it.

That's fantastic, I love it so much. You said that you like to stay true to the composer's original vision. Does that ever clash with some conductors' or directors' different interpretations? How do you deal with that?

Most of the time, we're doing things that were written by people who are long dead, so all we have to give us clues into what the composer thought of is the things that they wrote in the score, so it has happened. Of course, on occasion I've had directors who have asked me to deliver things the utter opposite of what I was actually saying. And that's always tough. There are times when I could sing things a little differently because I feel different, but when you've upended the actual meaning of the words — like, you're saying “I love you," but “I love you" with as much heavy sarcasm and ire and anger that you can muster. So, I always try as hard as I can to argue for the stuff that I think I absolutely have to have, and to try and give them as much as they're asking for in order to help them realize a vision for a production.

Do you listen to yourself?

Yes... [laughs] Not with a lot of pleasure! [laughs again] But it's funny because, I have said this before too, I am able to hear things that I do and understand that there are things I do well. I wouldn't have the career for as long as I've had it at the level I've had it if I wasn't doing things correctly, you know? But of course, we as artists are always prone to hear the stuff that we don't like or hear the things we're working on and dissect why something worked or why something didn't work and, like I say about reviews, if you get 49 reviews that say you sound like Caruso incarnate and one review that says you sound like a dying pig, you'll only remember the one that talks negatively about you. You won't remember the other 49 who are absolutely in love with you. And the same goes for my singing.

You've been very patient with your career and let your voice evolve naturally towards the heavier roles instead of pushing it too early. Have you always been this patient, and... does it have anything to do with being a Chicago Cubs fan?

[hearty laugh] What a great question! [laughs again] Well, okay, so, all right. So, yes, I've always been careful about the roles I took, and that has started from the very beginning of my career. I would say it was less about being patient and more about being careful, because throughout the whole course of my career, I've always tried at least one time a season to have one piece, that was outside of my regular Mozart core. I worked hard to make sure that I had one thing that caused me to step outside of my comfort zone, so that when I came back to it, I would have a new experience, and I believe it helped my voice remain flexible. Now, regarding the Cubs! Thank God — unfortunately, I was in Munich when they won the whole thing in 2016, so that was kind of a bummer, and I remember, on the day they won it, I had a show that day, but I'd stayed up to watch, and I finally had to go to bed at, I don't know, 4:30 or 5:00 in the morning, and the game was still going on, and I just said, “I just have to go to bed, I've got to at least partially honor my commitment to the theater,” because I had a show that night. Being a Cubs fan definitely requires patience, and I think they're kind of interesting this year, actually.

What are some of your happiest memories as a performer?

Matthew (center) with Nathan Gunn (left) and Wendy Bryn Harmer in The Magic Flute (Ken Howard/Met Opera)

Oh, wow. What a good question. For instance, every time I have sung Werther, I've been sad that it was over. Singing that part really fulfills me in a way that — the only other one that gets kind of close to it is Damnation of Faust by Berlioz. I also feel deeply that music for some reason. Those two things touch me in a deeper way. I have a lot of great memories of, I mean, doing that new production of The Magic Flute, the Julie Taymor one back in 2004, and I have to say, it was a very satisfying thing for me to go back to it last season, nearly 20 years later, and think, “Well, I can still sing this music, I'm still good at this," you know, which was very satisfying for me because it was almost 20 years later, I mean, some of my happiest things thinking about some of the singers from previous generations that I've gotten to sing with, people like Edita Gruberová and Jim Morris and Sam Ramey and Robert Lloyd and Tom Allen... Boy, I know I'm gonna forget people, but having had a chance to sing with that generation of singers, — having had these opportunities to be near these people and watch them work and watch them sing and understand that they still take it seriously — these things always brought me joy every time around. I've had a lot of great experiences in working with great singers and great conductors and great productions but I still always say, I've never done anything in my career that got close to being a dad. When I'm home, it's hard for me to give up any time here, I hate to spend a moment doing anything that's not with my wife or not with my kids if I can help it, so that's a very important part of my life and more important, really, than the job I do.

How do you balance life as a dad with being an opera singer, since you're frequently away from home singing?

Oh man, it's so hard. I try hard to make sure that when I'm here, I'm really here. I try hard to make sure that I'm aware of everything the kids are doing, and making sure that I understand that this one's got a baseball game, this one's got a swim meet, this one's got a piano recital, this one has a basketball game. I try to go to all these things, even if it means kind of overextending myself a little bit, to make sure that I'm soaking up all that stuff. If it means I only come home for a couple days sometimes — it would be so much simpler just to go from Vienna to Napoli when I have three days and just do that and spend a couple days relaxing, or I could go home, and some singers look at me like I'm crazy, but if I have a five-day break in Europe, chances are good that I'm going home, even though it's kind of expensive. I just spend the money so I can have the family time. Because if I'm out of the house six, seven, eight months a year, boy, I miss a lot! If I'm an absentee dad while I'm here at home, that's a real problem. So I try to make sure that I do all those things and be as much a part of their lives while I'm home as I can.

From your performance of “Danny Boy" at the Met's At-Home Gala, it's pretty clear that your family are mega-fans. That was so sweet! [Matthew laughs] Do your boys come to your performances?

Matthew with Pretty Yende in L’Elisir d’Amore (Karen Almond/Met Opera)

They do, they came to see Tosca. I didn't bring them to Don Carlos because it was long. The oldest one could have managed it, I didn't know how the other two would do. But they came to Medea in the fall, they've seen me do lots of things. Also, there was a moment — I can't remember if it was the Met production or if it was one they saw in a live stream of Elixir, when I had to slap Adina on the butt. Oh, man, I heard about that from my boys so hard. “Daddy, what are you thinking?? How could you hit her?!?" So, part of me is, like, “All right, I'm teaching them well, they understand that kind of thing is not correct and a behavior that shouldn't be repeated anywhere in the world under any circumstances," but on the other hand, of course, I had to laugh because of course they don't know that she's got, like, three skirts on, and the odds of her having actually felt my hand were small. But they don't understand that, and that's okay. Yeah, but I do bring them and I want them to be educated about opera. I hope that they fall in love with it. But I wouldn't qualify them exactly as superfans. They do love me, so that helps, but that moment that happened at the Met Gala, it was really spontaneous and completely caught me off guard.

Do you still like rock and roll? I know you were a big rock and roll guy before you found opera.

I definitely still like rock and roll; it's on in the car most all the time. I'm a fan, especially, of the rock and roll from the '60s and '70s, also of the '80s, less so of the '90s — somehow that era of music didn't touch me the same way — but I'm a fan of today's music too. I enjoy Coldplay, I mean, this is a band I really like and I've enjoyed every one of their albums, but if I'm listening to rock, I'm definitely more of the Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Van Morrison, The Doors kind of era music, and into the '80s with things like The Police and U2, U2 is also one of my absolute favorite, favorite bands, and I own all of their albums and I listen to all of them with huge pleasure. I like a lot of different styles of music, but yeah, rock and roll is probably the thing that owns my heart the most.

What advice would you give to aspiring singers too young to start formal training?

My advice would be to listen to the singers for whom 95% of what they had to give on the stage was vocal acting. And that style of singing, that style of vocal production is different from what we have today. And I do think there's great singing going on today, I have many colleagues whose singing I really, really revere. So number one, I would say, listen to the oldsters, the guys who recorded things in '40s, '50s, '60s. That singing is the singing that I have tried my hardest to emulate. Second thing, of course, would be to go as often as you can to the theater and see it, watch it, dissect it for yourself. Understand, look for ways to understand what's happening on stage and how it might relate to you as a singer. Try to treat your voice as well as you can, without asking too much of it, while you're too young to really appreciate and understand what the technique of singing really is. And the last thing I would say is learn how to like what you do. Learn how to like your singing. It's a huge tool to be able to listen to yourself and judge for yourself about the things that you did well and also critique yourself for the stuff that needs work.

Why is the Met special to you?

The Met is special to me because if it's not the greatest opera house in the world, it could only be in the top one or two. It's just a place where art is being made at virtually the highest level possible, and having had such a long association, 25-year association with that company, it's an immense source of pride, really. I love the people there, I have made a lot of great friends over all my years of singing there. I am aware that the people I'm stepping onto the stage with or into the rehearsal with are going to be A+ musicians and people who are at the top of their craft and people who I hope I'm gonna learn from and who might learn something from me. I love being associated with a theater that's as important as this one, and having such a deep and long-lasting relationship with this company has meant a lot to me. And I have enjoyed virtually everything I've ever done here. This place has offered me the possibility to sing with virtually everybody in my career, from Renée Fleming and Debbie Voigt and Susie Graham and Suzanne Mentzer and Ben Heppner and Sam Ramey and Jim Morris, and Dmitri Hvorostovsky, and on down the line are people like Artur Ruciński or Nadine Sierra, Ailyn Pérez, or Elīna Garanča, or — again, I'm leaving people out — they're not just people, they're the best people, and I've sung with them all here and really, I feel very lucky and blessed to have had the career I've had in this theater that's so important to arts organizations across America and even across the world. So, yeah, I have a very deep affection for this opera house, and I don't imagine I have 25 more years in me, but I do hope that my relationship with the theater doesn't end for a long time.

What can we do to keep opera thriving for the next generation, like your boys?

I think it's really imperative that we introduce opera to them all through elementary and junior high and high school. We have to expose them to this art form which incorporates all of our artistic ventures, really. It incorporates music, obviously, it incorporates theater, incorporates art, it incorporates dance. A lot of themes of operas are still relevant today. The group of people that understand opera in a deeper level are the people who are more than 40 or 50 years or 60 years old — to these people, opera still occupied a big part of our entertainment industry focus. I don't know where the disconnect happened, but we need to bring that back because we need a generation of listeners and watchers who get why opera is difficult, who get why opera is interesting, who get why this music is still important, why these themes are still important, and the only way to do it is to teach them. Everything gets a lot drier without music, and so I think studying music is still an important thing, and we need to prioritize it more.